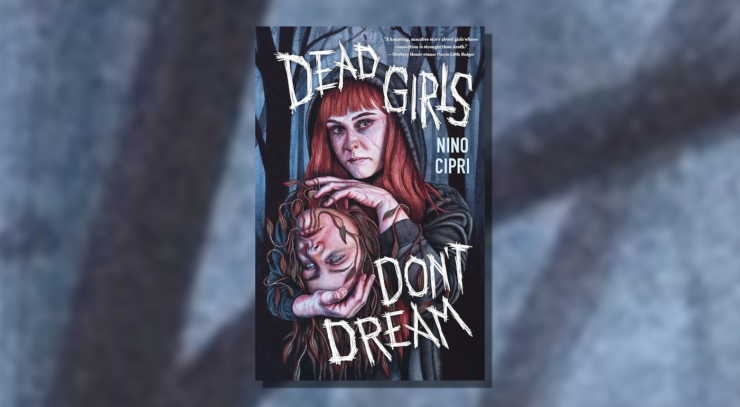

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from Dead Girls Don’t Dream, a new young adult horror novel by Nino Cipri, out from Henry Holt on November 12th.

There are rules for Voynich Woods: Always carry a whistle. Never go alone. Always come home before dark. And if anyone calls your name, don’t answer. Because everyone who wanders from the path is never seen again.

Except for Riley Walcott.

Riley knows better than to stray from the trail in the woods behind her uncle Toby’s house. But her little sister Sam breaks the rules in pursuit of a local legend, so Riley chases after her and discovers a knife-wielding figure and a waiting grave.

Madelyn lives deep in the forest. Subject to her mother’s strict rules, she’s forbidden from leaving home or using her magic—but one night, she risks everything to help a stranger who’s lost in the woods.

Riley is murdered in a strange ritual, Madelyn uses her magic to resurrect her, and their lives are immediately entwined in the gnarled history of Voynich Woods. Riley, who feels trapped in her small town but too afraid to leave, was never a believer, but now the evidence is taking root under her skin. Madelyn has the scars to prove how terrible magic can be, and longs for a life beyond her mother’s grasp. As the legends become all too real, Riley and Madelyn must confront their deepest fears to uncover the truth about Voynich Woods.

On the day her mother disappeared five years ago, Riley woke up somehow knowing she was gone, that Mom had never come home. Her bed was neat and obviously undisturbed. There were no clothes on the floor, no scatter of loose change, no lingering smell of cigarette smoke or the perfume she used to cover it.

It wasn’t the first time Riley had woken to her mother’s absence. She still remembered the first time, when she was eight and Sam was about one; she’d woken to Sam’s crying in the middle of the night, standing up in her crib and bawling. No Mom in sight. Riley had warmed up a bottle, then pulled her blankets into the other room and slept in her mother’s bed. Mom stumbled in a few hours later, loud enough to wake her, but at least Sam kept sleeping. Mom stood in the doorway watching Riley watch her, then turned and went to sleep on the couch.

But that was before. Anna Walcott had promised her eldest daughter that this time she would stay sober if it killed her, and Riley had believed her. She’d needed to believe her. So despite the dread curdling in her stomach, she scrambled the one egg left in the empty fridge and gave it to Sam with some toast for breakfast. She said Mom had left early for work but would probably be home for lunch. At lunchtime, Riley used the last of the bread to make mayonnaise sandwiches for her and Sam, and told her that Mom must have gotten the time wrong, but she’d be home for dinner, probably with McDonald’s as a surprise. At seven, she decided to walk with Sam to McDonald’s and pay for dinner with the emergency cash that Toby had given her the last time she’d seen him. It wasn’t much, maybe sixty dollars, but she’d wanted to refuse it, to say, We won’t need it, she said this time it was for real. But having faith in her mom was new, so she took it and told herself she’d give it back to Toby at some point, since she’d never need it. The cash lived in an ugly box that Sam had made in kindergarten art class, decorated with cutout pictures from old magazines, beads, and smears of glitter that still shed on Riley’s hands. The kind of thing kids were supposed to bring home to their parents, but she’d brought it to Riley. Riley kept the money in there alongside the fancy art markers and pens that Toby had given her for Christmas, kept the whole thing tucked away between her mattress and the wall. Hiding money and anything valuable from her mom was a deeply ingrained habit.

Buy the Book

Dead Girls Don’t Dream

But when Riley pulled out the box, there was only a ten-dollar bill and a handful of loose change rolling around next to the markers. Riley stared at the crease across Alexander Hamilton’s face and tried not to think about anything. Just squash every thought like a Whac-A-Mole game, so she wouldn’t have to wonder when her mother had found the emergency cash, or imagine what she’d bought with it. Ten dollars and change was still enough for dinner, and that was what mattered.

At McDonald’s, Sam picked at her food, leaving a mess of half-chewed chicken nuggets and cold, crumpled fries that made Riley want to scream a little, thinking of their empty refrigerator.

“When’s Mom coming home?” Sam asked.

Beneath the table, Riley dug the tips of her nails into her palms. “I don’t know,” she admitted.

“Can we call Uncle Toby?”

“No phone,” she said. Mom had had to cancel Riley’s phone plan when it got too expensive, though she’d promised it was temporary. The next paycheck had to go to rent and groceries, but the one after that—

“We could ask to use someone’s here?” Sam said.

A couple of weeks before, Mom had told Riley that she was on her last chance with her caseworker at the Department of Children and Family Services. “They’re looking for an excuse to take you and Sam from me,” she had said. “And I don’t know what’ll happen to the two of you if they find it.”

“Nah. We’ll wait a little longer,” she told Sam. “It’ll be okay.”

She braced herself for an argument, maybe even a full-blown tantrum. But Sam just nodded.

They went home and they waited, rewatching movies they’d borrowed from the library until they both fell asleep on the couch. Riley blinked awake after midnight. Mom still hadn’t come home.

That was it: She couldn’t negotiate with her mother’s absence anymore. Couldn’t keep waiting. She woke Sam up (“Mom’s back?” were her first words, and Riley had had to shake her head).

Riley’s phone was still inactive and useless, so they’d have to walk to the all-night gas station a mile away. She bundled Sam into a winter coat, then lifted her on her back and tied an extra blanket around her, because the temperature was hovering around 25 degrees. Her sister’s weight sat heavy on Riley, bent her forward. She thought of pictures she’d seen of child workers and war refugees. It never occurred to her to leave Sam behind.

Riley knew that she couldn’t think too much. She couldn’t think about what would happen to her and Sam, and she absolutely could not think about what had happened to her mother. If she started to think, she would panic. If she started to panic, she wouldn’t stop. She could only think about putting one foot down after the other.

She locked the door behind her and turned to start her slow, laborious journey. But instead of the county highway on the outskirts of Roscoe, Riley found herself among the tall, gaunt tree trunks in Voynich Woods.

Oh. Oh. This was a dream, and a familiar one: having to relive the whole stupid day when her mother left them, only something would go wrong. She’d talked this out in therapy years ago; the dream was her brain returning to an important moment in an attempt to integrate trauma, blah blah blah.

The only thing to do was walk, just like in real life. The only way out of this particular nightmare was through it.

She hadn’t been walking for long when someone spoke her name.

“Riley,” her mother whispered behind her.

She hadn’t heard anyone approach. There was nothing, and then there was her mother’s voice, which she hadn’t heard in…

Two versions of herself were laid over each other: Riley at twelve, whose mother had been gone twenty-four hours, anger and fear tangled together into a knot in her throat. But she was also seventeen, hadn’t seen her mother in five years. The anger and fear had calcified, a stone she had to keep swallowing.

Because her mother was dead. Wasn’t she?

That was the thing she could never say to Sam. Anna Walcott had been a broke single mom on welfare, with probation and court-ordered therapy for addiction; fifty dollars stolen from her oldest daughter might get her a bus ticket to Boston, maybe New York City, but it wouldn’t buy her a whole new life. The local cops didn’t have a great track record for solving cold cases, but if there’d been something to find, they would’ve found it by now, right?

“I missed you, Riley. Turn around and let me look at you.”

She shifted her weight to turn, then stopped herself. She didn’t want to look at her mother. She didn’t want to pretend that this was real, because when she woke up, she’d be left with all the rage and sadness and none of the momentary happiness.

Toby had some videos of Anna, old low-res ones taken on a digital camera when Riley’s mother was still a young woman in search of a good time—not happy, exactly, but not worn thin and threadbare by years of struggle. Early after her mother’s disappearance, Riley would watch those videos sometimes, try to melt the stone in her chest just enough to breathe around it again. She’d stopped at some point; the old videos had lost their magic. They made her feel worse instead of better. Numb.

She pulled that numbness around her now. Armor. Dug around until she found her anger and pulled that close to her as well. “Then you shouldn’t have left,” Riley hissed. “And if you wanted to come back, you should do it in the real world. Not a stupid-ass dream.”

Then she forced herself to start walking again. Luckily, she was on a wide path in the woods, level and packed. Sam was still sleeping on her shoulders, and Riley tried to shift her weight into a more comfortable position.

“Is that what you want?” her mother’s voice said. “A life where I stayed? Where you had the family you should have had?”

A few months before she disappeared, Mom had picked her up from school in a Jeep Wrangler that Riley had never seen before, Sam in a booster seat in the back, and punk music blaring from the speakers. Mom had told her it was a new holiday: Mermaid Day. You celebrated by driving to the ocean and spending the night on the beach. She’d bought them junk food for the hours-long drive to Portsmouth. They’d made a bonfire and ate s’mores for dinner, had a three-person mosh pit to the Distillers as the sun set, and then bedded down in the car, exhausted from a beautiful day.

But something had shifted during the night: The breeze coming off the water was cold and smelled oily, and Riley’s stomach hurt from all the sugar she’d eaten. She and Sam had slept badly, the air in the car was cold and damp, condensation fogging the windows. Sam had a nightmare that was so bad that she’d peed in her sleeping bag, and Mom had broken into tears while cleaning her up. And then—

Riley shied away from the memory, angry at her mom for making her think about it.

What did Riley want? She wanted to be left the fuck alone.

What came out was, “I want to go home.”

She heard someone take slow, considerate steps toward her. “Do you? Everything in the universe that you could wish for, and that’s what you want?”

The voice… didn’t sound like her mother anymore.

“Where is home?” the voice asked. “Your uncle’s house, where you were taken in like a stray cat? The moldy apartment where your mother abandoned you? Why can’t this be home?”

The thing behind her now felt as tall as the trees around it, as wide as the side of a barn.

Riley had stopped walking. She was still carrying Sam, gripping her sister’s legs around her waist tightly. What would Sam do if she woke up?

“You’re carrying your home with you, Riley,” the creature behind her said. It was closer to her now, close enough that she could feel its breath against her neck, smell loam and rot wafting from it. “A heavier burden than you’ll ever admit to yourself, isn’t it? What would you do if you could put it down?”

Riley shut her eyes, trying to remember how she’d gotten here. This was a dream, but she couldn’t wake herself out of it. She tried to retrace her steps—

“Riley,” the sly voice whispered to her. It drew her name out like a caress. “I could give everything you’ve dreamed of, if you just tell me what that is. Freedom, right? Escape? A place in the world where nobody knows you, nobody looks at you and sees your mother.”

Riley saw it, as clear as she saw the trees surrounding them: herself, a couple of years older, moving confidently through a busy city street. Tattoos printed up her arms and over her exposed chest like armor. Nobody looking at her like she was just another exhibit of tragedy or monstrosity in Toby’s barn. Distant, removed, and untouchable.

“I can give you that,” the voice promised. “Just set your burden down.”

Riley hissed through her teeth. “That’s my sister. She’s not—”

“You’ll have to leave her behind eventually,” the thing said. “I’m just offering a way to skip all the dramatics. Just let go.”

Riley wasn’t stupid. This had to be a trap of some kind. “What happened to me?” she asked. “How did I… I was in the woods. I saw—”

Her gaze searched through the trees around her, hoping she’d spot an escape. Instead, she found another pair of eyes staring back at her. A child, younger than Sam, staring at her from behind a tree. Wide-eyed, with dark, tangled hair. Fear in her eyes, looking at whatever stood behind Riley. The child shifted, and Riley could see two long, deep wounds that lay over her front. One ripped open her throat, while the other tore down the center of her chest. All around the edges of that terrible wound grew tiny white flowers.

Riley put a hand to her chest to pull her whistle out of her shirt. Three short blasts meant, Come find me. Come save me.

She felt something else instead, flat where the whistle was round, engraved instead of smooth. She was wearing a locket shaped like a heart, finely engraved with a pattern of flowers and vines, but old and tarnished, grimy against her fingers.

When she looked up again, the child was closer. She was staring at Riley with deep, fathomless eyes.

“Riley,” the voice said. “We’re running out of time. She’s found you. I’ve made this offer twice, and I’ll make it once more. What do you want?”

It would be so easy, she thought. To let go. To stop struggling toward an uncertain dream, to have it gifted to her instead.

“I want to go home,” Riley said again. Even though it was true, it hurt to say it.

The creature, when it spoke again, sounded as if it were smiling. “The old covenant, then. A wish, a secret, and a boon.”

“What? What’s a coven—”

“Because if you don’t want to set your burden down, maybe you wouldn’t mind if it became just a tiny bit heavier? A fair exchange to get what you want. A way home.”

The voice was her mother’s again, warm and rough from a decades-long smoking habit. She spoke in Riley’s ear, and she smelled like tobacco and amber perfume and sweat, the way she would after a long shift. There was no slur in her voice, no brittle anger, no stress. It promised adventure, the same way she’d declared it Mermaid Day on the way to the beach. We’re getting out of here, her mother had said. Nobody’s gonna stop us.

The locket was still in her hand. Riley squeezed it against her palm and nodded. “Take me home.”

Excerpted from Dead Girls Don’t Dream, copyright © 2024 by Nino Cipri.